From Endangered to Empowered: Our Journey Building Language and Speech Technologies for Middle Eastern Languages

The Middle East is like an intricately woven carpet, where each thread represents a distinct language, each color a unique cultural tradition. Just as master weavers create patterns that tell stories through their rugs, these languages weave together the rich narrative of the region. Yet many of these linguistic threads are fading, their colors dimming in the digital landscape. While languages like Arabic, Persian, and Turkish have established digital presences, numerous regional languages with millions of speakers remain virtually invisible in the technological landscape. As linguist David Crystal wisely noted, “An endangered language will progress if its speakers can make use of electronic technology.” This observation became the driving force behind my project, DOLMA-NLP: Developing Technologies for Middle Eastern Languages.

The Inspiration

As a speaker of Kurdish, a low-resourced and historically discriminated language, my academic and professional journey has been fueled by a deep-seated motivation to transform the technological landscape for under-represented languages. Throughout my long and challenging path, I’ve been acutely aware of the obstacles faced by marginalized language communities seeking digital representation and empowerment. Though my research has always aimed to be inclusive, I felt compelled to expand my horizons and deliberately focus on developing resources for all under-represented languages in the Middle East. This commitment led me to a fortuitous opportunity: the SILICON Practitioners Program at Stanford University in Spring 2024.

SILICON (Stanford Initiative for Language Inclusion, Computation, and New Opportunities) was established with the express purpose of supporting digitally disadvantaged languages throughout their digital inclusion journey, from basic encoding and keyboard design to advanced technologies like machine translation and AI development. When I proposed the DOLMA project, I felt incredibly privileged to be selected as part of the inaugural cohort of fellows. This acceptance represented the chance to finally launch an initiative I had envisioned for years. Being part of SILICON provided not only motivation from the program and fellow practitioners working on similar challenges but also helped me realign my priorities to fully commit to DOLMA’s mission. Read more on how this Stanford initiative seeks to bring more languages online or watch this interesting video describing SILICON’s mission:

The opportunity to work alongside others dedicated to digital language equity created a powerful foundation for what would become a transformative project for several Middle Eastern language communities.

Our Mission and Vision

DOLMA-NLP was built on three core pillars:

- Developing language technology for under-represented Middle Eastern languages

- Creating sustainable language communities focused on NLP

- Raising awareness about linguistic diversity in the region

Rather than pre-selecting specific languages, I cast a wide net through public outreach and community engagement. The eight languages that ultimately became the focus of our work, Mazanderani, Gilaki, Talysh, Zazaki, Hawrami, Southern Kurdish, Laki, and Luri, emerged organically through grassroots interest and community commitment.

This bottom-up approach reflected our philosophy that sustainable language technology must be driven by speaker communities themselves. While we initially received interest from other language communities, including Shabaki and Balochi speakers, these connections didn’t develop into the sustained collaboration needed for substantial progress.

The languages that flourished in the project collectively represent over 20 million speakers across the region, from the Caspian Sea coast to eastern Turkey and western Iran. Each brought unique challenges in terms of orthography, dialectal variation, and existing digital resources, but all shared a common need for technological support and recognition.

What made this approach particularly valuable was that it allowed communities to self-identify their needs rather than having external researchers determine research priorities. This created a foundation of trust that would prove essential in the later stages of our work.

Building Communities First

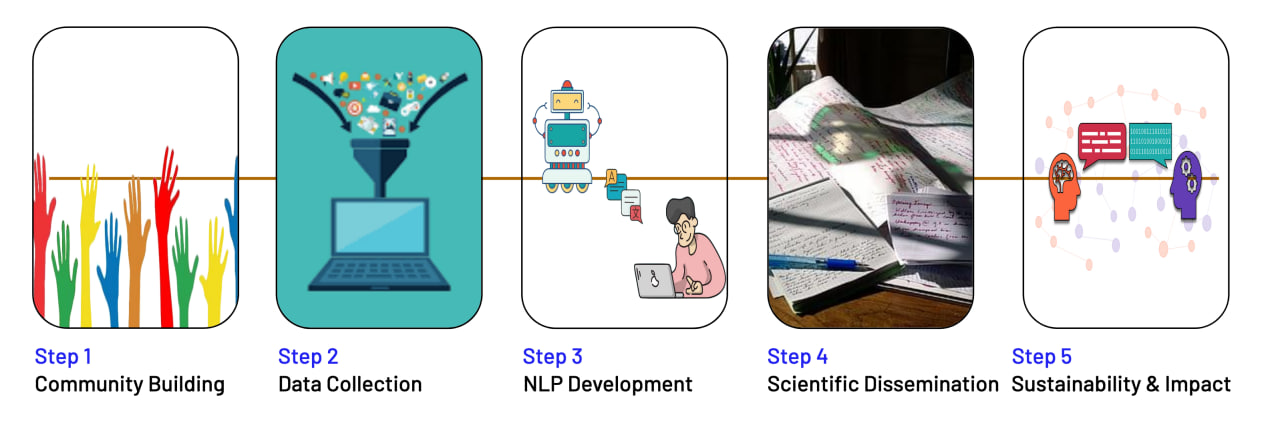

The first phase, which ran from August to October 2024, focused on community building. This wasn’t just about finding volunteers - it was about creating a movement. Our approach included:

- An intensive outreach campaign primarily via Telegram

- Public announcements through Twitter/X

- Direct outreach to academics, activists, and native speakers

- Cold messaging published authors and language experts

The response was encouraging, albeit mixed. We exchanged over 5,000 messages and assembled a team of more than 40 volunteers, with 30 highly active contributors. While language activists and native speakers were enthusiastic, we also encountered skepticism. Some questioned whether our work would inadvertently contribute to “cultural hegemony of Turkish language,” others wondered why anyone should care about “local” languages, and some even asked if we were working for a political entity.

In response to these concerns, I emphasized that DOLMA-NLP transcends political and cultural divisions. Even the project’s name was deliberately chosen as a unifying symbol—dolma, a stuffed vegetable dish prepared and cherished across all Middle Eastern communities, represents our commitment to celebrating what brings people together rather than what divides them.

Our mission is purely linguistic and technological, focused on empowering communities through digital tools regardless of political borders or cultural differences.

Despite initial hesitations, the shared vision of language preservation and technological advancement ultimately brought diverse communities together. As contributors saw the project’s genuine commitment to all languages equally, without preference or agenda, trust grew and collaboration flourished. This cultural neutrality proved essential to our success, allowing us to work across traditional divides that might otherwise have hindered progress.

Data Collection: Building Resources from Scratch

With our community established, we focused on creating a parallel corpus, a collection of texts translated across multiple languages. Our approach was deliberately community-driven with collaborative review processes at its core.

Throughout this process, I encountered a significant challenge: linguistic insecurity. Many translators had never imagined their language extending beyond daily conversations to formal translation from English. Some hesitated, uncertain if their language was suitable for such work. To address this insecurity and acknowledge the lack of standardization in many of these languages, I established an important principle: everyone was free to translate into their own dialect.

This freedom came with two guiding conditions: use the existing writing system or orthography of the language (when available) and prefer native vocabulary over loanwords. This latter point was particularly crucial as many of these languages are increasingly filled with borrowed terms due to their marginalized status. The result was a beautifully diverse corpus that captures dialectal variation rather than imposing artificial standardization.

Like any community-driven project, we experienced numerous challenges. Some potential contributors expressed verbal interest and created online buzz but provided little practical help. Others dedicated substantial time and energy to the task. Cultural and identity questions frequently arose; for example, Laki Kurdish speakers repeatedly requested that I specify “Kurdish” whenever mentioning “Laki” as “Laki Kurdish” to acknowledge their cultural identity—a request I honored throughout the project.

The ingenuity of the community often surprised me. One contributor leveraged their Instagram page, typically dedicated to cultural content, to crowdsource translations by posting a sentence or two daily and gathering translations from followers' comments.

The community-building process stretched across ten full weeks. While mostly rewarding, it was also exhausting—requiring countless conversations, calls, and explanations of our objectives. This intensive engagement provided the unexpected benefit of connecting me with fascinating individuals truly passionate about their languages. It also helped me understand the seemingly basic yet profoundly important problems these communities face in maintaining their linguistic heritage.

The results exceeded our expectations. We compiled over 50,000 sentences across 8 languages and 17 dialectal varieties. Hawrami speakers were particularly enthusiastic, contributing 14,572 translated sentences. Southern Kurdish varieties collectively contributed over 13,000 sentences, while Gilaki speakers provided 9,099. Each language community showed different patterns of engagement. Zazaki had fewer total sentences (4,172) but a high number of contributors (8), while Mazanderani had a moderate number of sentences (1,932) with 6 contributors. This diversity of participation highlighted the varying levels of community organization and digital literacy across language groups.

An Unexpected Turn: From Text to Speech

Perhaps the most exciting development came unexpectedly. The enthusiasm of the communities encouraged us to expand beyond text to automatic speech recognition. Thanks to their support, we collected over 40 hours of speech data comprising more than 28,000 utterances. I describe this unexpected turn in this blog post: Community-Driven ASR: Creating Speech Recognition for Low-Resource Middle Eastern Languages

Development and Scientific Dissemination

By October 2024, with data collection completed, my focus shifted entirely to research and development. The dual objectives became clear: develop effective machine translation systems and automatic speech recognition capabilities for our selected languages.

After thoroughly cleaning and organizing the collected data, I began the technical development phase. This work resulted in several openly-available resources and tools that communities could immediately begin using. More importantly, the research findings were documented in academic papers submitted to major computational linguistics and speech processing conferences (ACL 2025 and Interspeech).

These submissions represent more than academic achievements; they mark the formal introduction of these languages into the global NLP research community. Each paper documents not only the technical approaches but also the methodologies for community-driven language technology development that other researchers can adapt for additional under-resourced languages.

By March 2025, our progress had significantly exceeded our initial timeline. We had successfully completed the community building and data collection phases as planned. Both the NLP development and scientific dissemination were also largely complete, with a few papers submitted to major conferences representing the culmination of these efforts.

Looking Forward: The Future of DOLMA-NLP

As this phase of DOLMA-NLP concludes, the real work begins. Our parallel corpus and speech data provide a foundation for developing specific NLP applications: machine translation, speech recognition, sentiment analysis, and more. But technology alone isn’t enough.

The long-term success of this initiative depends on continued community engagement, institutional support, and integration with educational systems. These languages need not just digital resources but digital champions who will ensure the technology reaches those who need it most.

In the words of the DOLMA community (and represented by the project’s name), this work should be as nourishing and sustaining as the cultural dishes that bring people together. It should preserve what makes each language unique while connecting its speakers to global conversations.

The journey from endangered to empowered is not completed in a single project or paper. But with each translated sentence, each recorded utterance, and each new technological tool, these languages take another step toward digital vitality.